Shui Ka-chun, Hong Kong Activist, Dies

A social worker and teacher imprisoned for his activism, he later wrote about the toll of incarceration and worked to help others behind bars.

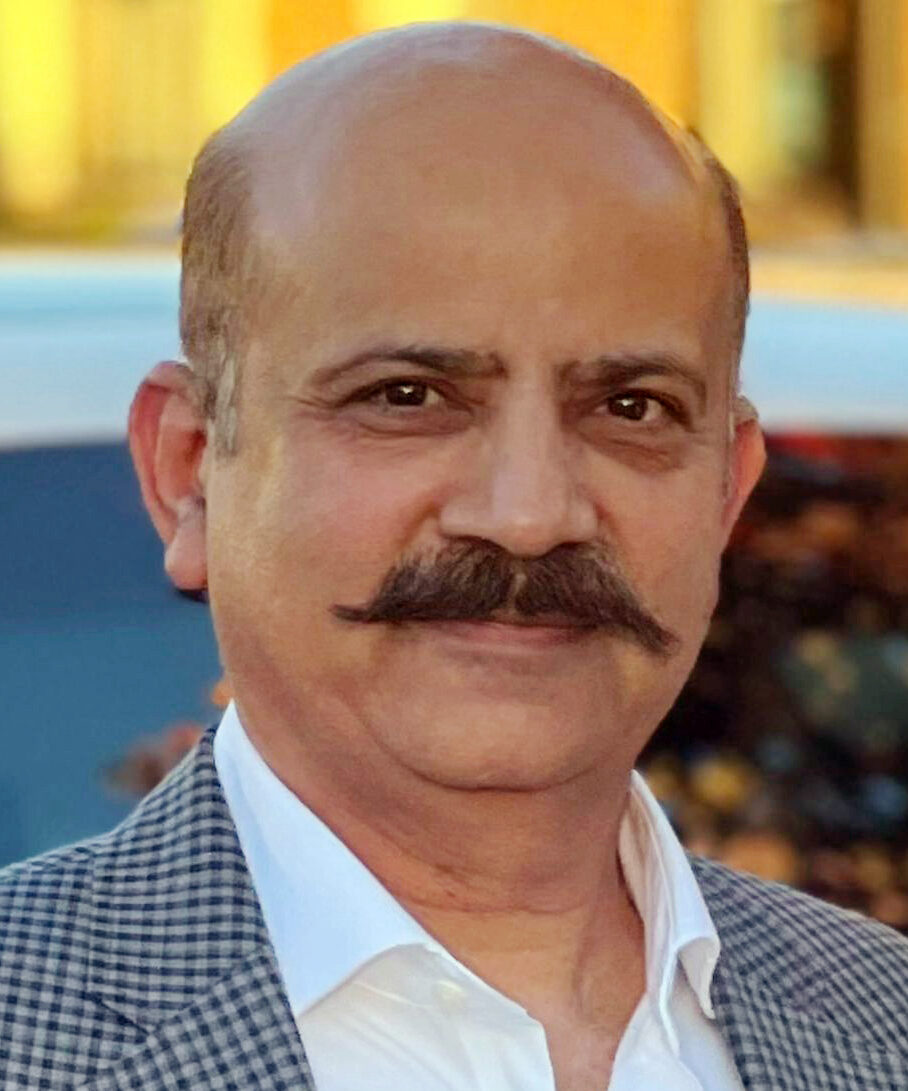

Shiu Ka-chun, a former social worker and pro-democracy lawmaker in Hong Kong who devoted his last years to helping protesters imprisoned after a crackdown on dissent, died Friday in Hong Kong. He was 55.

His wife, Kelly Hui, said his death, in a hospital, was due to stomach cancer.

As a social worker, civil rights activist and for a time as a legislator, Mr. Shiu pushed for the rights of the marginalized, but his participation in a protest movement landed him in prison. He later emerged as a crucial supporter of those incarcerated in the aftermath of a national security crackdown that began in late 2019.

Mr. Shiu was born in June 3, 1969, to a working-class family in Hong Kong. He studied social work at Hong Kong Baptist University, and after graduating started his career as a social worker supporting young people. In 2007, he started teaching social work at the university, where he became known for his engaging lectures. He also honed his voice as a commentator, writing newspaper columns that analyzed social issues through the lens of philosophy and sociology.

Mr. Shiu got involved early on in the 2014 civil disobedience movement, Occupy Central with Love and Peace, which demanded democratic elections for Hong Kong, a semiautonomous Chinese territory. He mobilized other social workers to take part in the protests that blocked traffic in the heart of Hong Kong’s business district. He reached out to people with disabilities or chronic illnesses, or who were homeless, helping to organize dialogues where they discussed what democracy meant for them.

In 2016, he was elected as a lawmaker. He focused on welfare issues such as poverty, homelessness and the conditions at homes for the elderly and people with disabilities.

In 2019, Mr. Shiu was convicted of public nuisance charges for his role in Occupy Central and sentenced to eight months in prison.

“I want to remind those who live in the dark to not get used to dark, not to defend darkness out of habit, and not to scoff at those who search for the light,” he said outside of the courthouse ahead of his sentencing.

Image

Chan Kin Man, a sociology professor who led the Occupy Central Movement, recalled sharing a cell with Mr. Shiu on the day they were convicted and seeing how his health had deteriorated. He said he had known that Mr. Shiu had diabetes and high blood pressure, and had been hospitalized in 2014 during the street occupations.

“I watched him lie in bed, unconscious and vomiting,” Mr. Chan said in a phone interview from Taipei, where he lives now.

“With his health in such a poor state, he still took part in so many political activities. I really respected him,” Mr. Chan said.

When he was behind bars, Mr. Shiu filed complaints about prison conditions, even at the risk of making himself a target of the authorities. His efforts led to some marginal change: Prisoners were allowed paper fans in the heat of the summer.

Mr. Shiu’s teaching contract at Baptist University was not renewed after his release from prison. He founded a nonprofit, Wall-fare, focused on helping people imprisoned after the 2019 protests. The organization paired inmates with pen pals to ease their isolation, and helped supply them with prison-approved toiletries and snacks.

Wall-fare was forced to close in 2021, as activism grew more risky. Mr. Shiu deflected questions from reporters about the reason for the closure and what it would mean for prisoners. “Tears are our common language,” he said.

In the years that followed, he wrote several books about the condition of Hong Kong’s prisons and the mental toll of incarceration, drawing from his own experience. He continued to post updates on social media, relaying snippets from his visits to former lawmakers and activists who were in prison.

In November, he posted a photograph of himself in a hospital bed wearing a mortar board, saying that he had had to miss his graduation from a master’s degree program in Christian studies for health reasons. Later, he wrote that he had been diagnosed with cancer, and that part of his stomach had been removed.

In his final weeks, he posted essays that he titled as musings from a “stomach-less” person. He wryly observed that tube feeding was difficult for someone like him, who loved food. He also shared his reflections on suffering.

“Resilient people are able to maintain a positive attitude and develop coping strategies despite the pain of illness, regulate their emotions, stay positive, and learn to live as normally and ordinarily as possible,” he wrote in mid-November.

“However, I also need to add a caveat: My body is out of sorts, I need space for rest. I will stop if I have to; please forgive me.”

Tiffany May is a reporter based in Hong Kong, covering the politics, business and culture of the city and the broader region. More about Tiffany May